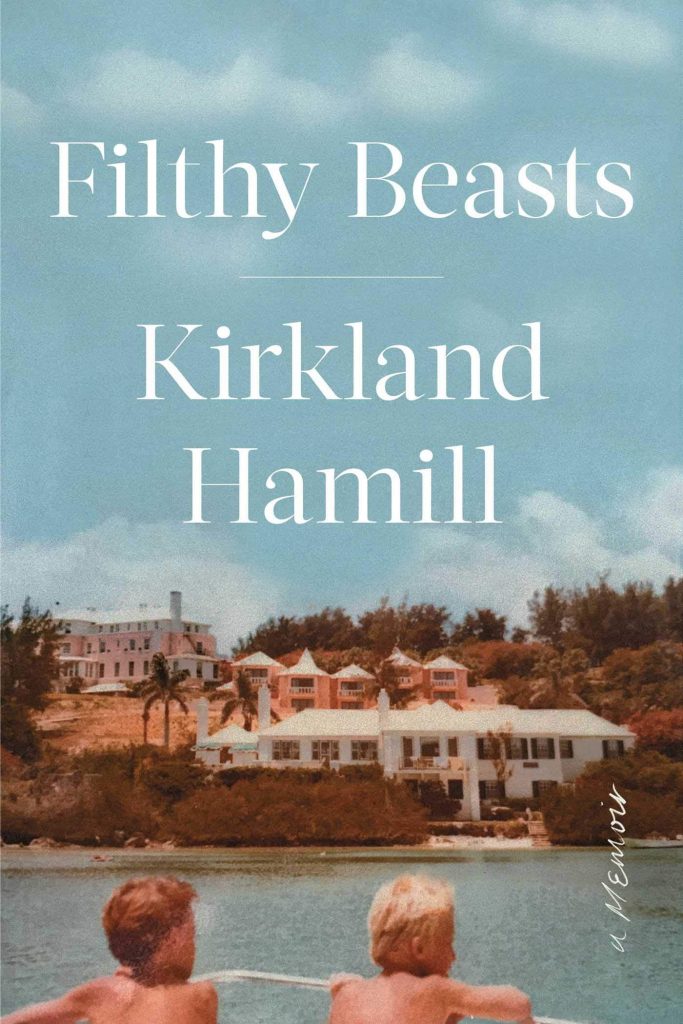

- Filthy Beasts a Memoir Kirkland Hamill Avid Reader/August, 2020. Running with Scissors meets Grey Gardens in this gripping, true riches-to-rags tale of a wealthy family who lost it all and the unforgettable journey of a man coming to terms with his family’s deep flaws and his own long-buried truths.

- By Kirkland Hamill RUNNING WITH SCISSORS meets Grey Gardens in this gripping, true riches-to-rags tale of a wealthy family who lost it all and the unforgettable journey of a man coming to terms with his family’s deep flaws and his own long-buried truths. “Wake up, you filthy beasts!”.

Subscribe on iTunes | Google Podcasts | Spotify

Watch Kirkland Hamill read an excerpt from the audiobook version of his memoir FILTHY BEASTS.Learn more: with Scissors meets Gr. Kirkland Hamill wrote his memoir Filthy Beasts which was listed one of the New York post’s best summer books for 2020. Kirkland’s memoir is about survival and recovery of his identity, memories and compassion for his mother let’s hear from Kirkland now.

I am delighted to introduce to you my friend and fellow Bermudian, Kirkland Hamill who has written his memoir ‘Filthy Beasts’.

Kirkland shares his story with a real honesty that is refreshing and courageous when it comes to the secrecy surrounding the family disease of addiction.

The New York Times, Jason Sheeler wrote in this review of Filthy Beasts:

“Wake up, you filthy beasts!” Hamill’s mother hollered to her three sons on school mornings. Those were the all-too-brief good years, before divorce and alcoholism took her under; before Hamill and his brothers’ lives took on a feral quality.

Survivor would be a word I would use to describe Kirkland however he is more than that … entering the rooms of Al-Anon as a 19 year old on the small island of Bermuda, and working diligently on learning healthier ways to cope and thrive in his life.

See full transcript of the episode below.

Intro: You’re listening to the Embrace Family Recovery Podcast. A place for real conversations with people who love someone with the disease of addiction. Now here is your host Margaret Swift Thompson.

Margaret: Welcome back in this episode I have the honor of introducing you to a fellow Bermudian and author. Kirkland Hamill wrote his memoir Filthy Beasts which was listed one of the New York post’s best summer books for 2020. Kirkland’s memoir is about survival and recovery of his identity, memories and compassion for his mother let’s hear from Kirkland now.

Margaret: How do you qualify as I say in the rooms and then you hear in the rooms, who’s your qualifier to your own family experience of this disease.

Kirkland: My mother certainly. There are a lot of family members who would qualify as Alcoholics but certainly for me, it was my mother.

Margaret: At what age Kirkland did you know mom had a problem? At what age did you realize this isn’t your norm?

Kirkland: Yeah it was probably my early teenage years. As you know it can be sort of a slowly developing thing. Where I came from a world where there was a lot of drinking and so that was just the norm to begin with. When it became a question of her behavior being different than even the people who were drinking really heavily, I think I started to recognize that in my early teenage years. I tell a story in the book about Christmas eve, she put a roast in the oven and I smelled it burning and I couldn’t find her. So we turned off the oven and I found her in bed asleep right you know, I interpreted it as her being asleep she was obviously passed out um and I recognize that that’s not something normal that happens on Christmas Eve where your mother drinks too much and passes out and forgets that there’s food in the oven so. That was probably when I got my first conscious inkling, I mean there are lots of in retrospect you know things before that, that are now obvious but um I think that’s when I really started to think OK something’s not quite right here.

Margaret: so I wonder if you relate to this when you say in retrospect ’cause obviously you were younger than I was when I was exposed to addiction in a primary relationship I was a young adult, well yeah. And so when I was told when the news came to me that the person I was involved with was an addict, unbeknownst to me it was like suddenly a bunch of puzzle pieces fit together and made perfect sense. And I could look back over our relationship and pinpoint now that makes sense. OK now I understand that I’m actually not crazy this was happening. But I didn’t want to see it believe it, acknowledge it. So did any of that happen for you when that night happened and you had the clarity that whoa this isn’t normal and you look back. Could you see things differently with that awareness?

Kirkland: I don’t think I thought about it in that way at that point. It was only I think when I got to Al-Anon at 19 when my own life was starting to fall apart because of, for the inability to or just not having grown up in a healthy environment and all of those things that you learn. You know and when I was on my own, I just didn’t have the tools to live a functional, healthy life and that’s when it really started to sort of fall apart to the point where I then had to figure out what it was that, why I was you know in this space that I was am and what I need to do about it. And you know the only thing I knew at that point was that I needed to get help, and it’s only in the getting of help and sort of the being exposed to people who’ve been through similar things that I then could start piecing it together. As I said that early teenage experience was just sort of one datapoint in thinking that something was wrong. I wouldn’t have pegged it as my mother is an alcoholic, I would just have pegged it as something’s not right here and I didn’t know the full extent of what that was until years later.

Margaret: it’s very interesting I think that many listeners will want to understand a young person’s perspective navigating it when it’s a parent. And as I’ve found in the years of working with people it is different for everybody right. It appears that your role in your family, and I’m curious if you would classify it this way, was a bit of a caretaker of sorts. In that you were trying to manage mom’s behavior and maybe even your siblings at times. Would you say that’s accurate?

Kirkland: Yeah we all played different roles. I was definitely kind of taking on the emotional hit of it and my older brother was reacting in a very angry, defiant way which was partially protective of us, against her. And I was somewhat defensive of her while at the same time trying to be as emotionally supportive for my brothers as I could be, with a pretty empty tank myself.

Margaret: Right.

Kirkland: So yeah, I think you know part of that is just the fact that I’m a middle child I think that has something to do with it. I think I was just more in tune emotionally than my brothers were at that point and my mother and I were very close. I mean she was I think, one of the things that’s difficult in when if you’re trying to help a child sort of figure out how to help their parents. The primary thing that what’s happening to me was that my mother was still my lifeline, I mean there was it wasn’t like as when I got to college and started to separate and live my own life. I then had to figure out how to live my own life but when you’re 13/14 years old you’re dependent on your parents. So, the instinct for denial is very strong. You can’t.

Margaret: Survival, wouldn’t you say?

Kirkland: Absolutely. You can’t think that there’s something so wrong that it’s going to imperil your survival. So you are, the way that you think about it has to be nuanced enough that it’s ultimately going to be OK or that she’s going through a difficult period. Or there are things that are happening that you don’t know about, that she will work through and get better again and part of that was just being naive about what addiction was and it’s very difficult. I still find it difficult to even diagnose addiction in a lot of people for some people it’s super clear for other people it’s very, there’s kind of a continuum of OK well this doesn’t seem particularly healthy, but does it rise to the level of addiction. To a certain extent I think that doesn’t really matter. As I came to learn if I’m having a problem with my mother’s drinking or anybody else is drinking, then I have to take care of my problem and they have to take care of theirs, if they want to. It’s not my business to do that. But certainly, when you’re a kid I think the desire, the as you said a survival instinct for them to be OK is such that there’s only so much awareness that you can have of it or that I had of it I should say.

Margaret: Absolutely and I also think Kirkland two thoughts from what you’re sharing It’s not just survival ’cause it is absolutely. But it’s, you’re a young person, underdeveloped who hasn’t got other people in a responsible role managing it well. So that is survival but it’s also this, you said earlier I think I was doing the emotional part right with the family. I was in tune with it. In my humble opinion there’s no doubt you were for you landed in al Anon in 19 you were connected to the emotions of it whereas a lot of people to survive it, emotions gone can’t do it, liability. I’ll be pissed off ’cause that feels safe and powerful, or I will use or numb or disappear from it, stay out of the house. And you found your way to help at a very young age as a man, young man unusual in Al-Anon and then also the age you found IT. How did that happen?

Who Is Wendy Kirkland

Kirkland: It was, well there are a few things that happened. My freshman year of college I just couldn’t function and I was well aware of the fact that I was using devices that just weren’t working anymore. I played on people’s sympathy a lot. I would use the stores of my mother and my parents, my upbringing too just sortof paint this horrible picture of what I was going through and really fed off of the sympathy that I got from it. To the point where that petered out, it didn’t work anymore people grew with their you know sort of eye rolled about it at some point like OK we got it, it sucks. So that kind of played itself out at the same time I met somebody who was a friend, a sort of a very interesting relationship which I talk a lot about in the book, of somebody who I really admired. It turns out I was in love with him, I didn’t think about it at that time that way. But he also was the type of person who only really wanted people around who he wanted to be around and at some point my shtick was just not doing it for him and he was kind of moving away and I thought I need to become the kind of person that he’s going to want to be with and as weird as that sounds as a motivating factor to get better because I was worried about what other people thought about me it was actually a very strong motivator. And then just realizing that I had nowhere else to go. I mean I was sinking so quickly. And I didn’t, I think one of the things about having this kind of emotional depth or capacity also means that I wasn’t able to turn a blind eye to things. I couldn’t bring myself to not see something, and I could see the appeal in that. I’m thrilled and feel very fortunate that I didn’t have that ability because it served me much better in the long run. But certainly, at the time if I could have figured out a way not to see something it would have been an easier way to go. But I just wasn’t wired that way and once I saw it, my first instinct was how do I fix it. And, of course like most people who go into recovery they’re thinking how do I fix the addict.

Margaret: Right.

Kirkland: So, I will be OK. Which as you know, and I know that is not how that goes.

Margaret: No

Filthy Beasts Book

Bumper: This podcast is made possible by listeners like you. Can you relate to what you’re hearing? Never miss a show by hitting the subscribe button now back to the show.

Margaret: So again a point you bring up that’s clarity for people listening who may never have given themselves help on the family side many people who end up in treatment for the disease of addiction end up in treatment when life’s falling apart and there’s no longer a coping mechanism that’s working there are pains, consequences and they get help. I believe the same is true for family members, we may get there via person in our life but unless we’re hurting enough we’re probably not going to do the work of Al-Anon recovery either.

Kirkland: Yeah, I think that’s true. I was terrified I was just I was scared. I was also ambitious. I mean that’s the other part of it. I could feel myself not having the tools in order to be a successful human being and that terrified me, and I thought OK. I need to figure out where these tools are so I can start building myself into somebody who has a fighting chance of being a functional successful person, and so I think there was a part of it that the ambition was part of it too like, I wasn’t, I couldn’t have just sort of gone down the path of falling further and delving further into drinking on my own or doing the things that I think happened to people. Because intellectually I was aware that that wasn’t going to get me to where I needed to go and even though so many instincts were pulling me in that, not instincts but so many compulsions were pulling me there I mean my family was riddled with them. I had to intellectually orient myself to OK these are the things that you’re going to need to start doing and you’re going to and having, developing a certain amount of humility around that was also important. That I am going to have to accept that I need the help and I’m going to have to trust that when I find people who know how to help me that I will start paying attention to them and listening to them in doing what they’re suggesting. I could always turn another direction if I if at some point it’s not working but I was at a state where I was like OK, I’m done so whatever you got for me I’m going to listen and I’m going to start doing it and hopefully things will get better.

Margaret: So you’ve mentioned your book a few times and I have had the privilege of reading it as have many other people. What made you want to write the book?

Kirkland: There are a few answers to that too. The first was when I was going through a lot of the stuff that happens in the book, I was alone, and I remember thinking I want to witness to this. And I realize now that that wasn’t necessarily the kind of witness that I wanted when I was in college. You know sort of the oh woe is me witness. I wanted not to be alone in it and being in writing the stories and telling the stories of what was actually happening it was a mechanism from me no longer to be alone with it. The second reason was just the compulsion to write. I think people who write books or finish books I should say have that compulsion there is something within them that just is not settled, at ease unless there’s some process of putting it down on the page and making sense of it. So I got very interested in creating a narrative around everything that had happened. I didn’t necessarily do it at the time as catharsis. It was just kind of the interest of wanting to kind of look back at the beginning and get to the end of the story, but not the end of the capital S story but the end of the small s story and really understand what it happened through the whole thing and delve deeply enough into why I acted that way when I was 19, why I acted that way when I was 25, why I didn’t come out until I was 30, why didn’t know I was gay until I was 30. What are the reasons for that. How what was happening to me and happening around me that kept me from knowing that for so long. I became very interested just as kind of probing myself as a human being to understand what that was. What the byproduct of it was. When I was done, I had this very solid understanding of what had happened. Which gave me a lot of power to be able to then place it in some sort of context. And you know with addiction, with everything there is no cure but a very solid base on which I could then take what I’ve learned and build on that for the rest of my life.

Margaret: I found it, I said to you, I think the description that fits from my perspective is you took the big beautiful red velvet curtain that many of us put up to protect the world we’re in. And you pulled it aside and showed a very real unvarnished picture into this family disease of addiction. And in my humble opinion that takes great courage to speak but even more courage to write. Did you have trepidation about putting the book together?

Kirkland: No. I think partially that was because in my early days of Al-Anon and you and I have talked about this before. I recognized shame as I could almost see it as this kind of separate force. This separate thing that you either took on or you shed and if I was as long as I was clouded by it, caked in it, mired in and influenced by it, I was still struggling. I was still sick. I was still, so at some point I decided I’m just going to reject it I’m going to reject shame and part of that is just deciding that whatever story I have to tell is a very human story. And I understand on some level that even if people don’t tell their own personal stories they’re not going to read mine and think of it a freak or, oh I can’t believe you know he’s talking about his sexuality or that experience that he had or whatever. I think most people are going to read it and go I have a story like that. They may not be putting it down on paper. They may not even be telling a lot of their friends but they’re going to be able to relate to it because all of it is human. So, I just made a decision that it wasn’t just a decision it was always, also recognizing the power of it. The more that I revealed and told and didn’t hold on to as shameful or something to hide, the more powerful I felt, the more present I was, the more happier I was, the lighter I felt, and I really liked that feeling. And the book is kind of the ultimate expression of that. Like if I tell this whole truth and do it knowing that they’re going to be people, and there are, I’m uncertain there are, they’re not telling me about it which is perfectly fine. Who probably think that I shouldn’t have done it. That you know you shouldn’t be telling your family secrets and you should, you know that’s sort of breaking some sort of rule I am OK with them having that reaction. I’m probably even OK with them if somebody wants to talk to me about it because I also, part of the recovery piece is recognizing that if somebody disagrees or has a different perspective or a different value about that, but that’s perfectly OK as well it doesn’t have to be mine and as soon as I kind of internalized all of that I just felt pretty free to tell my own story.

Margaret: And that’s exactly what you did. Obviously when we tell our own stories as family members there are people involved who had the illness there are other family members, and that balance of telling my story and letting them tell their own is one that I hear from many people is a struggle. Like I’ll talk to people in early recovery who want to get their own help but they’re afraid to go to an Al-Anon meeting because then it outs the person in their life who has the disease.

Kirkland: Yes.

Margaret: Did you ever go through that fear of going in the room in case that was then associated with mum or anyone else in the family?

Kirkland: Certainly, initially there’s the trepidation. One of the things that I discovered which you know all too well is that when you walk into those rooms it’s almost like this magic bubble descends and it is as anonymous as the title suggests. You are there. Everybody is in your same boat so it’s almost you know there’s nobody pointing fingers ’cause you’re all in the same all pointing, your pointing at yourself. You all there for the same reason and the integrity around the anonymity of it is very intact and strong. So I absolutely understand that there are a lot of people who aren’t going to want to write books about it, but being going to a meeting an Al-Anon meeting or an AA meeting that anonymity is guaranteed. So once I really understood that I was no longer worried about the island being small enough, where people would then start gossiping about my mother. My mother, this is the other thing, that’s just the way it is, most people who encountered my mother or anybody around my mother knew she was an alcoholic. There was no, it wasn’t like she was this pristine well-mannered person and then ran into the closet drank a bottle of vodka and became a raving lunatic behind doors. I mean she was out there and pretty much living how she wanted to live, and she really didn’t care what other people thought about that. So she was pretty, most people who were in that circle new my mother and knew exactly what was happening with her.

Margaret: I found going to a meeting a really good humbling, ego reduction experience, That terminal uniqueness that we’re the only one who’s ever gone through this or that or the other and also like you said looking around the room and knowing people there have been through something similar if not very similar to what I have is one of the most wonderful parts of finding your community of support.

Kirkland: Well, it’s kind of eerie ’cause you live for a long time thinking that you’re in this unique experience. It’s so painful and so difficult and nobody could possibly understand what it’s actually like, and then you go into the room and everybody knows intuitively without you having to explain a thing. And like you said that’s, it’s jarring at first ’cause you’re kind of like, you know I thought I’ve been living in this kind of rarified existence and it turns out it’s actually quite common, and all of these looney tunes things that are happening are actually components of almost everybody else’s story. You know there are themes and variations all over the place, but the basic pieces are pretty uniform and pretty the same, you know almost to a weird extent is how alcoholism and addiction kind of impacts how people behave and both the alcoholic and people around the alcoholic.

Robin Hamill Bermuda

Margaret: Yeah and to me hearing in both sides of the coin an example and going oh done that, wow I forgot that or been there. Totally true, you did it too. You know it’s like it’s so reassuring and yet troubling. And yet like I wish more people would find it because it’s so much less painful when you find those people who get it.

Kirkland: Well it’s part of the disease, is that you think you can do it on your own, you think you can figure it out on your own and you don’t, there’s also people I think who go into those rooms and they think OK with that I was 19. I was a man and most of the people there were women in there 50s and 60s and probably most 19 year old men would have looked at that and gone you know I’m just in the wrong spot, this doesn’t fit. Um I think I was also fortunate or maybe just needy enough at that point to have looked at all that and said I don’t give a shit, I mean if these women have something to teach me then I’m here for it. And I’m not worried about the optics at all I think I again feel lucky that the optics of these things didn’t take me off of my path. I decided at some point that I don’t give a shit about the optics ,what people will think about me what people think about any of it. I’m going to stick to a path that I know is making me better and how other people feel about it again I’m you know we spend so much time worrying about how other people may look at something and most of the time people aren’t thinking about it that much they aren’t thinking about you and the ones that are really kind of fixated on it and are deciding that your whatever you’re doing is not you know what you should be doing those are people you probably don’t want in your life anyway so when you kind of play it out I think that was that was another strategy that really helped me was playing things out. Like going OK what if my friends found out what they say? How would I feel about it? What would happen the next day? What would happen the day after that? Am I going to be OK? Are they still going to be my friends? Yes, yes, yes. OK then what am I worried about. I’ve done a lot of that just sort of every time I have something that feels like insecurity. I think to myself OK let’s play this out a little bit. What am I really scared of? What can potentially happen? And usually when you stare it down it’s not much of anything. Certainly nothing that rises to the level of you derailing your own wellbeing and your own recovery in getting better from a disease that’s a very difficult disease to navigate.

Margaret: Do you think you got some of that from your mum?

Kirkland: Yeah it’s been interesting in the inscription on the front of the book says I,it’s dedicated to my brothers and my mother and I said she was fearless, ferocious and funny. And I said you taught me how to survive you, and she did not care. I mean she did, and she didn’t. Externally she didn’t care what people thought and I think that became a. She influenced me in a huge way related to that, she, there is a dark side to her not caring which was that she was not open to getting help. She was not. She didn’t have the humility or the self-awareness to realize that she needed it. So, I took the good parts of it and I left the other ones which is also an Al-Anony way to go.

Margaret: Absolutely.

Kirkland: You take the stuff that works, and you leave the rest of it

Margaret: Please join me again next Sunday when Kirkland and I talk more about his quote “you taught me how to survive you” and we will further discuss the stigma of addiction, enabling and of course family recovery.

Outro: I want to thank my guest for their courage and vulnerability in sharing parts of their story. Please find resource is on my website embracefamilyrecovery.com

This is Margaret swift Thompson until next time please take care of you.